The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) recently released its proposed ‘Government Procurement Rules’ 4th Edition (the 4th Edition) for consultation. Once implemented, the 4th Edition will replace the ‘Government Rules of Sourcing’ 3rd edition (the 3rd Edition).

On 31 January 2019 we released this article, introducing those changes that MBIE is particularly interested to receive feedback on, the timeframes for submissions and how submissions can be made. Submissions are now closed but it is still important for all participants in public sector procurement to be aware of what the proposed changes are and how these may affect them.

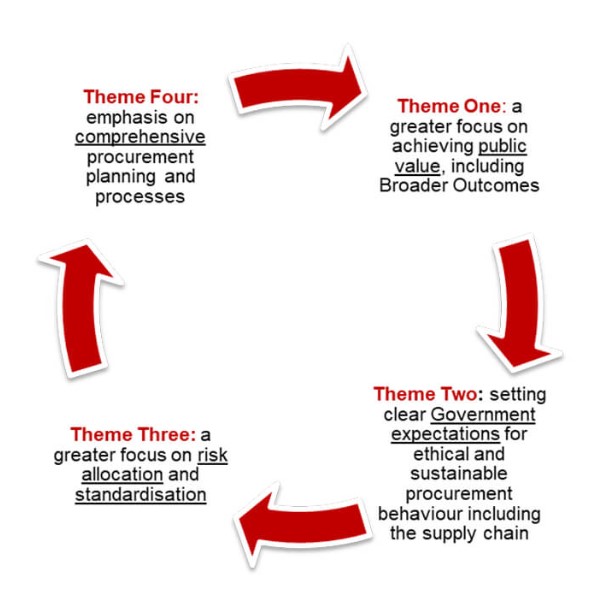

This article now examines these key themes and provides our key observations and some suggestions on how the industry can front-foot the changes. In the first section of this article, we have summarised four key themes to the changes. Further on, we provide more context and our suggested approaches to those parties likely to be involved in public sector procurement.

Summary of changes

Theme One: a greater focus on achieving “public value”, including Broader Outcomes

The most prevalent feature of the 4th Edition is MBIE’s drive to leverage procurement activities to achieve ‘Broader Outcomes’, which are the secondary benefits (such as environmental, social, economic or cultural) generated from a procurement activity. The term “value for money” no longer features in the 4th Edition – instead, the emphasis is now on “public value” which the Rules explain to mean “considerations that are not solely focused on price, for instance what benefit a procurement could bring to the local community or environment”.

Theme Two: setting clear Government expectations for ethical and sustainable procurement behaviour including the supply chain

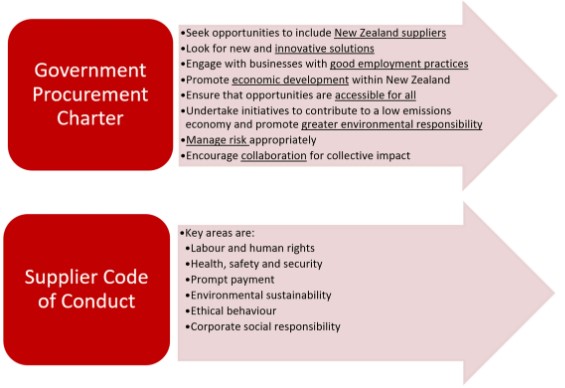

The 4th Edition introduces two new documents: the Government Procurement Charter (the Charter) and the Supplier Code of Conduct (the Code). The Charter and Code set out Government’s expectations of agencies’ and suppliers’ conduct in procurement activities. Agencies are required to have in place policies which incorporate the Charter. Suppliers are expected to use the Code as a minimum standard for its conduct generally. While the Code is not mandatory, agencies have the ability to remove suppliers who offend the Code.

Theme Three: a greater focus on risk allocation and standardisation

The 4th Edition acknowledges that good procurement is about being “risk aware, not risk averse” and for the first time directly addresses risk allocation by requiring that agencies “manage risk appropriately” and that agencies must not “transfer all risk to the supplier”. The 4th Edition also contemplates that Treasury will develop standardised contracts for infrastructure projects exceeding a total cost of more than $50 million and that Treasury must be consulted in relation to any material modifications to these standards.

Theme Four: emphasis on comprehensive procurement planning and processes

The 4th Edition places increased emphasis on procurement planning and regular review processes. This includes requiring agencies to produce an annual Procurement Capability Index self-assessment and developing comprehensive procurement plans for each proposed project.

Once implemented, the 4th Edition will set higher standards on all participants across all stages of the procurement process. The Rules are not intended to create a ‘box ticking’ exercise but instead genuinely facilitate improved procurement processes and activities to achieve the best possible result over the whole-of-life of the goods, services or works being procured.

We now set out our further observations and suggested approaches for public sector procurement participants.

Some further background

The Rules are the Government’s standard of good practice procurement. The Rules focus mainly on the process of sourcing, rather than the full spectrum of a procurement lifecycle. For certain Government agencies, compliance with the Rules is mandatory. For other Governmental bodies (including local councils), compliance with the Rules is not mandated but is encouraged.

So why have the Rules? Well, the Rules intend to:

- Guide public agencies to procure responsibly, achieving public value

- Provide consistent and transparent standards to give everyone confidence in the integrity of Government procurement

- Encourage commercial practice

- Support economic development

- Build high-performing public service

The 4th Edition is not a complete re-write of the 3rd Edition. For instance, large sections of the 3rd Edition remain substantively untouched, including in particular the processes to be followed by agencies when procuring under the Rules.

However, four key themes have emerged from the changes proposed to the 3rd Edition and our view is that they have the potential to shift the landscape of public sector procurement and industry behaviours. These four themes are:

Theme One: a greater focus on achieving public value, including Broader Outcomes

The most prevalent feature of the 4th Edition is MBIE’s drive to leverage procurement activities to achieve ‘Broader Outcomes’ and other “secondary benefits” from a procurement.

Previous editions of the Rules placed emphasis on achieving “value for money” and, while value for money can have different meanings to those in the industry, this term is embedded in both public and private sector procurement vocabulary. The 4th Edition no longer refers to “value for money”; in fact, this term no longer exists in the 4th Edition.

Instead, “value for money” has been replaced with “public value”. However, swapping out these terms has not been a simple “copy and paste” exercise. The 4th Edition goes much further. While the 4th Edition retains that “public value” is about getting the best possible result from your procurement, public value now expressly includes “considerations that are not solely focused on price, for instance what benefit a procurement could bring to the local community or environment” or, in other words, the “secondary benefits” from a procurement.

The key mechanisms under the 4th Edition that enable and/or mandate these “secondary” procurement benefits to be achieved are:

- First and foremost, through the introduction of new Rule 16, making it mandatory for each agency to consider, and incorporate where appropriate, ‘Broader Outcomes’ when purchasing goods, services or construction works. Broader Outcomes are defined as the secondary benefits which are generated from a procurement activity and can be environmental, social, economic or cultural. Under Rule 38, Notices of Procurement must describe any Broader Outcomes that a supplier is expected to deliver or an agency is seeking to achieve and under Rule 46 an agency must award a contract to the supplier that has either offered the best public value, including Broader Outcomes, over the whole of life of the goods, services or works, or if price is the only criterion the lowest price.

- Secondly and linked to the above, Cabinet and Ministers may now designate contracts against a specific priority outcome. In such circumstances, agencies must include requirements in their procurement process relating to the relevant priority outcome/s. To give effect to these priority outcomes, agencies must conduct sufficient monitoring of designated contracts to ensure suppliers’ contractual commitments are actually delivered and reported on. Four initial priority outcomes, and designations, have been mandated as follows:

- Next are the amendments to the ‘Principles of Government Procurement’ and the introduction of the ‘Government Procurement Charter’ (discussed further below). Agencies will be required to have policies in place, and to ensure that their staff are trained in and their procurement practices reflect, the Principles and the Charter. The secondary procurement benefits are embedded throughout the Principles and the Charter and should (and are actually required to) therefore be forefront of mind in agencies’ procurement decisions and activities.

- Finally, through amendments to Rule 3, agencies are given comfort that awarding a contract to a New Zealand supplier presenting public value, including Broader Outcomes, does not cut across discrimination provisions for international competition. Agencies are now empowered to “choose local”.

Theme Two: Setting clear Government expectations for ethical and sustainable procurement behaviour including the supply chain

The second notable addition to the Rules is the introduction of the Government Procurement Charter (the Charter) and the Supplier Code of Conduct (the Code).

The Charter and the Code set out Government’s expectations of agencies’ and suppliers’ conduct in procurement activities:

In terms of the Charter, as identified above the Rules will require agencies to have in place policies that incorporate the Charter and train their staff in it. Procurement practices will also need to reflect the principles of the Charter.

The Charter’s companion piece, the Code, provides a minimum standard that the Government expects from all suppliers, with agencies being given the ability to remove suppliers who offend the Code. The proposed Rules also signal that agencies could include their suppliers’ commitment to the Code within their delivery contract.

MBIE has also signalled an intent to pay closer attention to the relationship between a prime contractor and its supply chain, through:

- new Rule 25, which will require agencies to ask that its prime contractor meet certain procurement standards in its subcontracting and should consider how to flow down expectations around Broader Outcomes to subcontractors. The standards should be consistent with good procurement practice, as outlined in the Principles, the Rules, the Government Charter, the Supplier Code of Conduct, the priority outcomes set out in Rule 16, and other procurement guidance; and

- new Rule 51(2), which will require agencies to encourage their suppliers to pay their subcontractors promptly by ensuring suppliers offer subcontractors no less favourable terms as the ones they receive from agencies. MBIE has identified within Rule 51 that improving payment times and practices is a priority for the Government and, through guidance notes, provides a number of mechanisms for doing so.

Theme Three: a greater focus on risk allocation and standardisation

The Rules (both 3rd and 4th Editions) acknowledge that good procurement is about being “risk aware, not risk averse”. However, in the last 18-24 months and in particular following the implementation of the 3rd Edition, risk allocation has been the topic of conversation in both public and private sector procurement. Contractors in particular have voiced concern with the levels of risk being transferred in both public and private sector procurement and in the apparent re-writing of standard form contracts.

For the first time, the proposed Rules have addressed risk allocation head on, in particular:

- through the new Government Procurement Charter. Under the Charter, the Government directs agencies to “manage risk appropriately”. In particular, the Government directs that responsibility for managing risks should be with the party – either the agency or the supplier – that is best placed to. Agencies must not “transfer all the risk to the supplier”; and

- through Rule 65, where Treasury will develop standard form documentation to be used as the basis for any infrastructure contract, where the infrastructure exceeds a total cost of more than $50 million. Any material modifications will require consultation with Treasury.

Theme Four: Emphasis on comprehensive procurement planning and processes

The 4th Edition will place increased emphasis on procurement planning and regular review processes:

- Agencies will be required to plan under new Rule 15 to the extent appropriate based on the size and complexity of the particular procurement. Good planning is described as including market analysis, engagement with other agencies to seek collaboration opportunities, and considering what priority and broader outcomes can be achieved. A procurement plan should be developed to include key project information, a sourcing plan, any exclusions or exemptions, contract information, risk and probity, and a timetable. The 4th Edition also introduces a process for annually reviewing the value thresholds for when the Rules apply, with the threshold decreasing to $9 million for new construction works as of 1st October 2019.

- New Rule 70 will require that in planning for new construction works, agencies will have to apply the Construction Procurement guides. If an agency does not follow the guides, it will have to produce documented evidence detailing the rationale for this decision. Agencies considering the procurement of infrastructure with a cost of more than $50 million will have to consult and work with the Treasury during the procurement, following the Treasury’s advice and using their documentation. In previous editions of the Rules, this requirement was confined to Public Private Partnerships.

- Agencies will also have to produce an annual Procurement Capability Index self-assessment and submit this to MBIE. This assessment will enable an agency to identify areas where additional focus or improvement may be required. It will also allow MBIE to develop a cross-government view as to procurement capability and areas where more support is needed. Agencies will also have to produce, and renew biannually, a Significant Services Contracts Framework report to be submitted to MBIE. Significant service contracts are those that concern services that are critically important an agency’s business objectives or pose a significant risk or would have a significant impact on the agency, economy or New Zealand if it failed.

Key observations and suggestion

1. Front-footing. The 4th Edition will undoubtedly impact the way in which the private sector will need to tender for opportunities and deliver awarded contracts, and the private sector should therefore look to front-foot the changes signalled in the Rules.

- For example, in terms of tendering activities, suppliers should expect to see evaluation criteria in tendering opportunities focusing on the secondary benefits (e.g. Broader Outcomes) of the agency choosing the particular supplier. It would be prudent for suppliers to start turning their mind to not only the extent to which they can achieve public value for an agency but also how they can demonstrate they can and will do so.

- During delivery, suppliers should also expect to be monitored by the respective agency as to the achievement of the Broader Outcomes and compliance with the Supplier Code of Conduct (a failure of which may have default ramifications). We suggest that suppliers begin to think about becoming ready to comply with the Supplier Code of Conduct – this may require development of internal policies (and training) for supplier staff and subcontractors and getting ready to update subcontracts to flow through compliance with the Code.

2. Subcontracting. Government is signalling a clear intent to pay attention to the relationship of prime contractors and their supply chain. For example, we identified above that payment terms are a key area of focus with agencies being required to encourage prompt payment terms downstream. Suppliers may wish to look at their subcontracting payment terms, keeping a close eye on Rule 51 and the guidance notes within that Rule.

3. Resourcing. An inevitable function of regulation is that, for agencies, resources need to be allocated to plan, deliver and monitor compliance with the Rules. For example, we have identified in Theme Four above Government’s emphasis on comprehensive procurement planning and processes. Similarly, the private sector will have a role to play in achieving compliance with the Rules both in tendering activities and project delivery. For example, compliance with the Supplier Code of Conduct as noted above and achieving secondary procurement benefits in the delivery of projects. At least in the short term, suppliers will need to upskill on the Rules and, in the longer term, be in a position to comply with obligations imposed on them pursuant to the Rules. In the context of the well-documented shortfall in resourcing in the industry, it will be interesting to see how the public and private sectors can resource to comply with these requirements.

4. Standardisation. The industry has spoken out about the need for standardised construction documentation. As identified above, Rule 65 indicates that Government will be developing a suite a standardised documentation for major projects. We look forward to seeing the proposed approach on standardisation, including recognition that, for each contracting party, “one size” will not necessarily “fit all”.