Adapting to climate change is the most significant issue facing our generation. Decisions need to be made on how we adapt – what we protect by soft or hard mechanisms, for how long, where we say no to new development, and when and how we retreat. How we adapt is a complex problem – with many stakeholders, trade-offs, costs, and alternative consequences to consider. It is also a problem that affects us all, with the majority of our cities and urban areas close to the coast or located in low lying areas. The Auckland Anniversary floods, Cyclone Gabrielle and recent flooding in Dunedin and Clyde are a reminder of the power of the environment and the damage that it can cause. If we do not act now, we will continue to build in places that are subject to sea level rise or hazards, putting lives and investment at risk. To be effective, it is essential that climate adaptation policy has cross party support and provides a long-term framework for change.

This is the first in a series of articles addressing where we are in our climate adaption journey, the evolving climate adaption policy settings, and the actions required at the local level to establish and implement adaption plans. This article focusses on the first aspect – where are we at?

Our current framework under the Climate Change Response Act

The Climate Change Response Act 2002 (CCRA) has been around for two decades, and initially focused on the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions in order to meet our international obligations under the United National Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Kyoto Protocol. The CCRA has continued to evolve as new agreements are entered into internationally (i.e. the Paris Agreement).

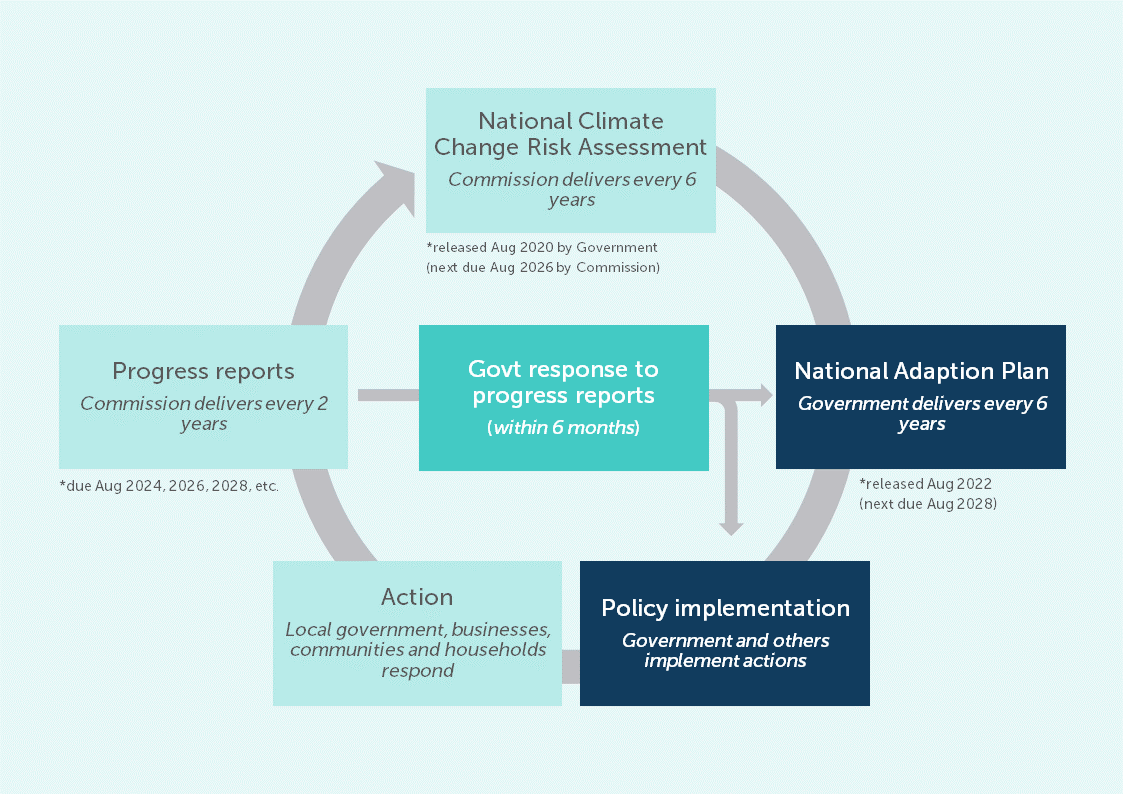

In 2016, the National government of the time, asked a group of experts across the private and public sectors to form the Climate Change Adaptation Technical Working Group. The Working Group provided a stocktake of where we are at in our climate change journey, and a report of recommendations to help build our climate resilience. These reports were published in 2017 and 2018 respectively, emphasising the urgent need for action, and informing new adaptation policies in the Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act 2019. The national direction delivered in this Act resulted in a high-level policy framework, consisting of a National Climate Change Risk Assessment (NCCRA) (first published in 2020) and a National Adaptation Plan (NAP) (first published in 2022). Each NCCRA and NAP is required to be delivered every six years, and a subsequent progress report delivered every two years.

Figure 1. The climate adaptation policy cycle set out in the Climate Change Response Act 2002 [1]

The NCCRA identifies the risks and opportunities, uncertainties and gaps resulting from natural hazard risks in New Zealand. The NCCRA informs the goals and outcomes of the NAP, which is required to set out New Zealand’s long-term adaptation strategy and actions to be taken across key priority areas.

The 2022 NAP focused on the following four priorities for action:

- Enabling better risk-informed decisions: Requiring access to up-to-date and accurate information, tools, methodologies and guidance on natural hazard risks.

- Ensuring our planning and infrastructure investment decisions drive climate-resilient development in the right locations: Reducing exposure to hazards by effective planning, urban design and management in legislation or regulation.

- Adaptation options including managed retreat: Educating and enabling consideration of the full range of adaptation options available to communities, to encourage local investment in climate resilience.

- Embedding climate resilience in all government strategies and policies: Encouraging action across five outcome areas, including the natural environment; homes, buildings and places; infrastructure; communities; and the economy and financial system.

The 2022 NAP identified that adaptation is a process of assessing risk, implementing the plan, monitoring and evaluating how effective the plan is, and adjusting as necessary. The first essential steps are to assess the risk and have a plan in place.

We are not doing enough and require urgent action on adaptation planning

The Climate Change Commission has recently released the first Progress Report on the NAP, tracking where we are at in implementing the strategies and outcomes specified in the 2022 NAP. It has found that the risks from climate change are rising and are insufficiently addressed by current adaptation action in New Zealand. The Progress Report finds that progress has been slow, and the NAP has not driven adaptation at the scale or pace that is currently needed. The following issues remain unclear:

- the funding mechanisms available to pay for adaptation;

- the roles and responsibilities required to implement adaptation;

- the data and information to inform adaptation;

- failure to address issues of equity; and

- obtaining the right knowledge, skills and expertise.

Under the current policy framework, there are no mechanisms to update the 2022 NAP in response to the recommendations of the Progress Report, and the next NAP is not due until 2028. Recommendations to improve the NAP include that it would be more effective as a living document instead of requiring a static document to be updated every six years. The theory is that a living NAP would provide the flexibility necessary to adapt to an ever-changing environmental context and preserve the ability to update courses of action as new data and information becomes available. It was noted that while the 2022 NAP contained general adaptation principles and objectives, comprehensive strategies with measurable outcome targets or milestones with set timeframes, are required to motivate action now.

In the absence of clear national direction on adaptation, local councils have used other tools at their disposal

The New Zealand Coastal Policy Statement (NZCPS) adopted in 2010 introduced clear and directive policies to avoid subdivision, use, and development in areas of coastal hazard risk. It includes policies that require the identification of land subject to coastal hazards over at least 100 years, to avoid redevelopment or land use change that would increase the risk of adverse effects from coastal hazards, and to avoid increasing the risk of social, environmental, and economic harm from coastal hazards. These policies are clear and directive. However, the Department of Conservation review of the effect of the NZCPS on Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA) decision making in 2017 [2] found that implementation of the coastal hazard policies has been challenging and controversial for some communities. Challenges identified were data availability, community, iwi and stakeholder values, and financial constraints. The review found that further national guidance was necessary.

Under the RMA, local authorities are also tasked with identifying areas subject to hazard risk in their district plans, and are required to control any actual or potential effects of the use or development of land for the purpose of avoiding or mitigating natural hazards. Councils are also required to have regard to any NAP when preparing or changing a regional policy statement, regional plan or district plan. Recently, local authorities realised that their hazard management needed updating when enabling intensification to give effect to the National Policy Statement on Urban Development 2022 (NPS-UD) and have taken the opportunity to update hazard overlays in their district plans contemporaneously with intensification plan changes. However, identifying natural hazards is of limited benefit to building our resilience, if we do not have a plan in place on how we will mitigate risk (if we can, and for how long), or if managed retreat should occur (and how and when). The result is that we now have more extensive hazard overlays and ‘risk’ categories in district plans that create uncertainty for developers, infrastructure providers, landowners and insurers who are seeking to make future investment decisions.

The Government has recently announced that the RMA will be replaced by two Acts – one addressing urban development and the other the environment. It is not clear at this stage if climate change adaptation will be incorporated into both Acts, or subject to its own separate legislation. The Government has also announced as part of the suite of new and amended national direction, that this will include a National Policy Statement on Natural Hazard Planning. It is also anticipated that national direction is going to have significant weight under the new RMA regime.

At this stage, key parts of the puzzle remain missing – namely comprehensive national direction on how we undertake hazard planning, and how mitigation or managed retreat will be undertaken and funded. Principles need to be developed at a national level to provide clarity, consistency and fairness, but plans must also be prepared and implemented at the local level with engagement and buy in of the communities affected. Cross party support is also critical to ensure certainty of implementation over the long timeframes (decades) that plans will need to be implemented.

Recommendations to inform our national adaptation strategy have just been released

Minister for Climate Change Simon Watts established an inquiry in May this year, led by the Finance and Expenditure Select Committee (FEC), consisting of members of parliament across the political spectrum with the goal of arriving at an enduring and long-term approach to delivering a climate adaptation framework.

The purpose of the inquiry is to develop and recommend high-level objectives and principles for the design of a climate change adaptation model, to support the development of policy and legislation to address climate adaptation.

For this purpose, the FEC was tasked to consider the following topics:

- the nature of the climate adaptation problem New Zealand faces;

- frameworks for investment and cost-sharing;

- roles and responsibilities; and

- climate risk and response information-sharing.

The FEC reported back on 1 October 2024, and its findings and recommendations will be the focus of our second article in this series.

In our third and final article, we will address what needs to happen at the local level, including unpacking the Dynamic Adaptive Pathways Planning (DAPP) approach supported in the Coastal Hazards and Climate Change Guidance released by the Ministry for the Environment in February 2024. The DAPP ’10-step decision cycle’ is expected to be utilised by local councils undergoing long term adaptative planning and decision for coastal hazards.

Footnotes

[1] Climate Change Commission Progress Report: National Adaptation Plan - assessing progress and effectiveness of the first national adaptation plan (He Pou a Rangi Climate Change Commission, August 2024)

[2] Review of the effect of the NZCPS 2010 on RMA decision-making (Prepared for the Minister of Conservation by the Department of Conservation, June 2017)

This article was co-authored by Imogene Jones, a Solicitor in our Environment team.