Overseas, greenwashing trouble is brewing. Banks have made headlines for signing up to a global climate pledge which allowed them to invest unlimited amounts in coal mining and coal power despite promises to tighten the lending rules. In response, the European Central Bank declared in late 2022 that banks face litigation if they do not keep their climate pledges or meet targets they have announced. In Germany, the police raided Deutsche Bank’s asset management arm following whistle blower claims that the company was misleading investors about green investments. The German regulator alleged that ESG factors were not taken into account in a large number of investments.

Turning to the Pacific, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission launched a crackdown on greenwashing in October 2022. It will review over 200 company websites to identify misleading or deceptive ESG claims with possible enforcement action to follow.

Against this backdrop, and the everincreasing importance New Zealand consumers place on sustainability credentials [1], we should be in no doubt that greenwashing will be front of mind for New Zealand regulators. The regulators have already been carefully scrutinising greenwashing claims, putting in place a variety of legal frameworks and guidelines to make ESG claims more transparent and accessible, and to clamp down on misleading and deceptive ESG claims. Investigations, enforcement actions and complaints in this area are likely to be on the rise in 2023 and beyond.

Financial Markets Authority (FMA)

In mid-July 2022, the FMA conducted a review of managed fund documentation for integrated financial products (financial products that incorporate non-financial factors, such as ESG factors, alongside financial factors) (IFP funds). The FMA identified issues with the quality, utility, and accessibility of the information that IFP funds provide to their investors in required disclosures.

The FMA found that despite releasing its ‘Disclosure framework for integrated financial products’ in 2020, “Managers of IFP funds [still] had a lot of work to do and that the FMA now expected them, assisted by their supervisors, to take the necessary care not to mislead or confuse investors with greenwashing”. Some key issues identified in the review were that the funds did not adequately explain what IFP funds exclude and why, nor their approaches to positive screening (seeking to invest in companies that support their ESG policies) such as investing in clean energy.

More generally, we can expect to see the FMA using its powers under the fair dealing provisions in the Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013 in relation to misleading and deceptive claims, and unsubstantiated representations where an entity has overstated its ESG credentials. And with the new climate-related financial disclosure regime upon us for January 2023, this new regime will be a new frontier of litigation for the financial sector. We may in time see new claims being driven by AI tools such as ClimateBert which is a tool designed to analyse climate-related corporate disclosure.

Commerce Commission

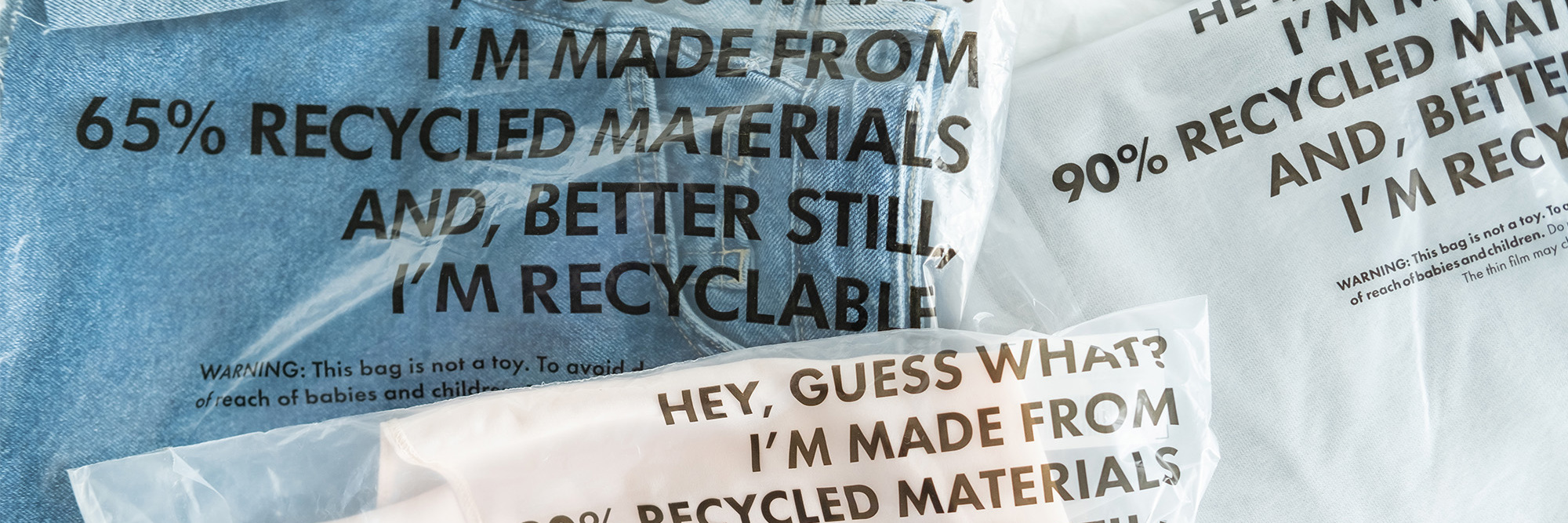

To date, the Commerce Commission has largely been focused purely on environmental claims rather than broader ESG claims. It released guidelines in 2020 on composition claims (recycled content,‘free-of’ claims, and organic), production claims (made with renewable energy, sustainable materials and durability claims, carbon off-sets/carbon neutral) and disposal claims. We have been involved in several requests for information regarding environmental claims but there is currently no significant public enforcement action being taken by the Commerce Commission in relation to greenwashing. We expect this to change.

We can expect more advertising complaints as well, either in the courts, investigations by the regulators or the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) Complaints Board. Last year the ASA considered a complaint about a gas company which was “going zero carbon”. The Board found that this was a “socially significant issue” requiring “a due sense of social responsibility” which had not been met. There was no timeline or detail about how “zero carbon” would be achieved and therefore the board decided this was an unsubstantiated environmental claim and the advertisement was to be removed.

Finally, greenwashing, like any representation to a large group of people, creates significant class action risk. In the United States, greenwashing claims have been made against H&M which allegedly led customers to pay inflated prices for items which H&M said were produced more sustainably than competitors. This same class action formula could apply to ESG claims in relation to any other products and services.

The risk of ESG claims are heightened as ESG terms are not well defined and often mean different things to different people. Sustainability metrics can also cause issues when these are not fully disclosed and explained, and the data source used is not properly detailed. This uncertainty is ripe for litigation risk and, for each entity, will require solid strategy from management and the board to celebrate ESG achievements and targets, while also keeping faith with customers and staying on the right side of the regulators.

Footnotes

[1] In a 2019 survey by the New Zealand Sustainable Business Council, sustainability was a mainstream concern for 87% of New Zealanders and at least 47% said they cared about sustainability when choosing a brand/product to purchase.