The Controller and Auditor-General John Ryan’s office has recently conducted an assessment of four local councils to understand the progress each organisation has made towards planning for climate change. Ryan has urged that there is still more work to be done in respect of adaptation. In a recent interview, he noted that “despite the absence of a legislative and financial framework to support some of the more significant climate adaptation options, councils are getting on with the important task of talking with their communities about what matters to them and what adaptation options looks like”. [1]

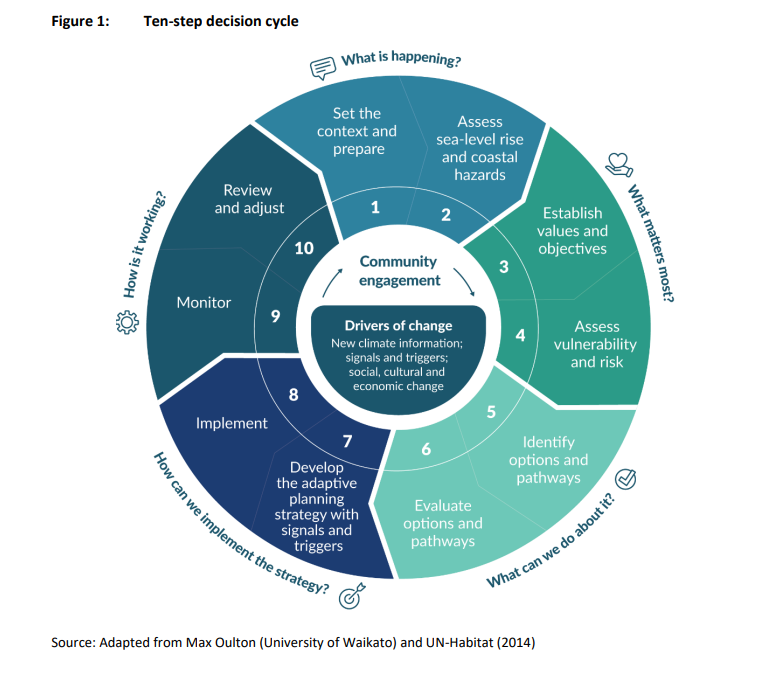

In this third article of our climate change series, we address the kinds of collaborative actions that are required at the local level to enable adaptation. Specifically, we unpack the Dynamic Adaptive Pathways Planning (DAPP) approach and provide recent examples of its implementation. DAPP is outlined in the Coastal Hazards and Climate Change Guidance released by the Ministry for the Environment in February 2024. The guidance presents a ’10-step decision cycle’ which is recommended for use by local councils undergoing long term adaptative planning and decision-making for coastal hazards.

You can read our first article, discussing where we are at in our climate adaptation journey, including our evolving climate adaptation policy settings, here, and our second article, unpacking the Finance and Expenditure Select Committee (FEC) inquiry into climate adaptation, including considering roles and responsibilities here. The Government has also recently responded to the FEC report, and confirmed that adaptation is a critical challenge and action is a priority.

|

Dynamic Adaptive Pathways Planning (DAPP) directs process over outcomes

DAPP can be described as a process for developing multiple actions that can be implemented over time. It is an example of a DMDU method (Decision Making under Deep Uncertainty) which aligns multiple adaptation planning options with preferred pathways or actions that can be implemented once specified thresholds, triggers or conditions have been met.

Generally, a choice is made to start with short-term actions that do not close off future pathways. Short-term actions are often temporary solutions which are easy to implement, such as soft defences and sea walls. In response to a trigger, a community should switch to long-term actions (e.g. relocation) before the short-term actions reach the end of their “shelf-life”. [2] This approach enables decision-makers to manage risks more effectively when there are gaps and uncertainties in the best available information. Future weather events and their outcomes are inherently unpredictable, and variables are exacerbated by future unknowns regarding the scale of global effort to reduce emissions. For these reasons, it is desirable to build flexibility into plans and procedures.

A ‘10 step decision cycle’ to adaptation planning

Because Aotearoa is an island nation, coastal hazards are one the most significant risks that we face. To assist regional and territorial authorities with climate adaptation, the Ministry for the Environment (MfE) released coastal hazards and climate change guidance in 2024. That coastal guidance was led by key researchers on climate change adaptation, Dr Judy Lawrence and Dr Rob Bell.

The guidance incorporates the NZSeaRise research programme’s updated sea-level rise (SLR) projections released on 2 May 2022. NZSeaRise draws on internationally assessed SLR projections for various global warming scenarios, based on the latest information from the 6th Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). It combines those projections with local vertical land movement data (subsidence or uplift in the land), assessed at 2km spacing, to obtain the ‘relative SLR’ projections. Assessing relative SLR projections is an emerging but reliable science that continues to be refined. A mapping tool is available online for both the public and for planners to review.

MfE’s coastal guidance recommends a multi-evidence approach is taken to assessing relative SLR projections as part of a precautionary approach that utilises DAPP planning. Multi-evidence approaches incorporate more than one stream of evidence from multiple perspectives including scientific, cultural (i.e., mana whenua), and experts and locals experience and judgement. MfE’s coastal guidance is generally accepted as national guidance for local and central government. All experts involved in land-use planning, resource management, building consenting, asset and flood risk management and infrastructure planning should refer to the guidance when undertaking work in the coastal environment. It may also be used by planners, engineers, lawyers, community engagement facilitators, policy analysts, scientists, insurers, lenders, and those in the finance sector.

We unpack the step-by-step decision process below:

Step 1: Set the context and prepare

Planners must consider the law related to hazard management, and what is considered ‘best practice’. As we identified in our first article in this series, we have limited national guidance and funding available at this stage of our adaptation journey, and councils will be required to innovate and undertake their own regional and district level hazard assessments. In hazard management, planners will need to consider the worsening of hazard events, their increasing frequency over time, and progressive changes to the coastal environment including relative SLR. To confine the scope of hazard risks within communities, multi-disciplinary teams will need to be established and engagement with stakeholders should occur early.

Step 2: Assess sea-level rise and coastal hazards

Uncertainties and gaps in the science available to assess hazard risks present a significant obstacle to effective climate adaptation. Scientists have not confidently determined the rate of ice sheet loss that is expected in the future, and there are unknowns regarding future warming and relative SLR vertical land movements (earthquakes). In some locations, SLR will be exacerbated by sinking land and adaptation will be required sooner. As the science is refined and updated, councils and planners will need to monitor developments and adjust modelling accordingly. Dr Bell recommends that as part of the precautionary approach, “medium confidence” scenarios are used in SLR assessments.

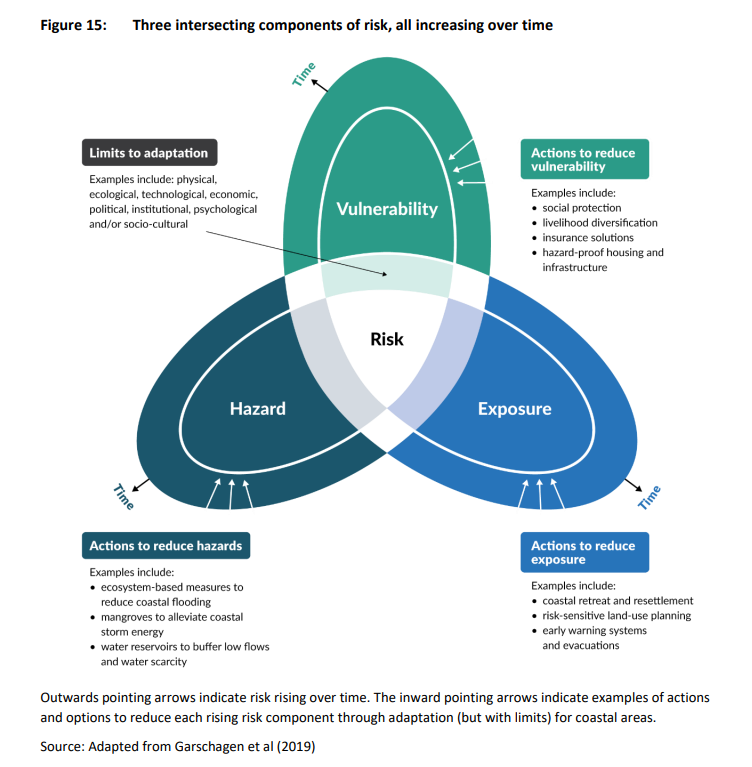

Step 3 and Step 4: Establish values and objectives and assess vulnerability and risk

To assess risks, planners will need to understand the nature of a hazard, and a community’s vulnerability and exposure to the hazard. Stakeholders’ values are crucial to implementing effective adaptation and will influence DAPP planning. Communities can be expected to have different appetites when it comes to bearing individual risk. It is likely that owners of primary residences will be more vulnerable to risk than owners of secondary residences, including holiday homes. Beyond considering the risk to physical things, other types of natural and intangible values (e.g. spiritual or cultural needs, or tikanga considerations) may also influence the objectives for DAPP planning. Early community engagement to establish values and objectives will be key to successful outcomes when it becomes necessary to implement adaptation options.

Without community buy-in, councils may be exposed to costly and prolonged legal action, as seen in the Awatarariki Managed Retreat Programme at Matatā. In 2005, intense rainfall caused debris flows into the Awatarariki fan head. These flows destroyed 27 homes and damaged 87 additional properties. Homeowners were allowed to rebuild on the promise of future protection. However, after seven years of exploring engineering solutions for a debris dam to protect the community, experts backtracked as this option was no longer viable. In 2019, Whakatāne District Council moved ahead with managed retreat due to the high risk of loss of life in the ‘red zoned’ area. A voluntary property buyout system was established to incentivise homeowners to sell and relocate. Funding for property acquisition was agreed between Whakatāne District Council, Bay of Plenty Regional Council and the Department of Internal Affairs. However, any homeowners who were unwilling to sell their properties were destined to become ‘illegal’ residents. The Bay of Plenty Regional Council and Whakatāne District Council made complementary plan changes to extinguish existing use rights and implement new zones, overlays and rules to ensure residential activities in the red zone were prohibited in the district plan. Unfortunately, adaptation and managed retreat planning were not organised in advance, meaning there was little scope to reduce negative social outcomes, delaying closure for homeowners. Ultimately, legal action was taken to the Environment Court on the legality of the plan changes, including if the plan changes were contrary to s85 of the RMA which provides that a plan provision can be challenged on the grounds that it would render an interest in land incapable of reasonable use. The appeal was resolved by settlement and the final family left the area in March 2022.

|

Step 5 and Step 6: Identify and evaluate options and pathways

Multiple adaptation options should be considered for a period in the short, medium and long term, over at least a 100-year period. DAPP planning should utilise a combination of different adaptation strategies, including the following:

-

Protect: Build defences to protect property, i.e. through stop banks, seawalls and sandbags.

-

Avoid: New development should not occur in areas prone to hazard risk.

-

Retreat: Relocate people, infrastructure and property away from areas prone to hazards.

-

Accommodate: Reduce the risk of damage by raising the floor level of buildings.

As noted in MfE’s coastal guidance, “each type of adaptation option has different lifetimes and will have different performance limits. In general, avoidance strategies should be considered first in coastal settings, to ensure that protect and accommodate options do not become the default approach without consideration of the known ongoing and progressive risk from SLR and storm surge.” [3]

Step 7: Develop the adaptative planning strategy with signals and triggers

Once palatable options are established to reduce risk to a community, appropriate signals or triggers should be created within flexible timeframes or as a means of responding to specific natural events. MfE’s coastal guidance specifies that triggers must be relevant, measurable, timely, reliable, convincing and pragmatic. [4] For example, for coastal flooding an appropriate trigger may be when a specific relative SLR height threshold is reached, or the frequency of flooding events has reached a high frequency return rate (i.e. 1 in 50 years). For coastal erosion, it may be when the dune-line reaches a certain distance from a house. Other non-technical reasons may also be influential, and a community may choose to relocate because of climate anxiety and/or low financial or social tolerance to a risk.

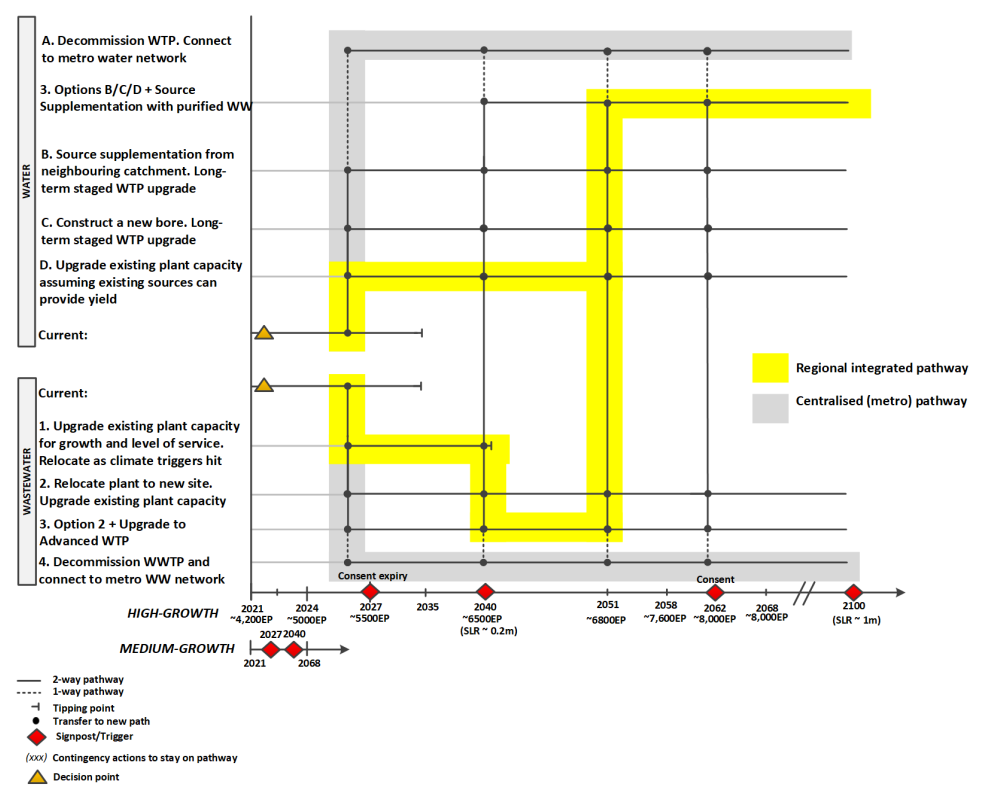

The Watercare Adaptive Water and Wastewater Infrastructure planning document is a good example of how Auckland Council is applying the DAPP approach. [5] This is presented in infographic form and involves developing a series of actions over time, with specific triggers or “tipping points” based on environmental indicators such as SLR and the frequency of flooding events and consenting expiry timeframes (e.g. when the present water take and effluent discharge consents expire).

When these indicators reach the agreed-upon thresholds, the council can implement additional or alternative actions to prevent severe damage and accommodate predictions that may have eventuated (e.g. raw water sources being provided to treatment plants declining in volume and quality due to population growth decrease in an area).

Chosen future pathways at the current point in time have been mapped within the framework of possible options in order to provide a baseline for future planning. This method will ensure that short-term decisions remain aligned with long-term resilience goals and allow for adjustments as conditions evolve.

|

Step 8: Implement

Planners can incentivise action on adaptation through utilising our current frameworks. New provisions in district plans could give effect to the solutions achieved through DAPP planning. For example, plans can specify that new development is prohibited in specific overlays or precincts, provide for subdivision restrictions, enable defences, or require raised floor levels as a standard for residential or commercial development. Natural hazard risk information could also be identified on Land Information Memorandums. However, implementation of complex solutions such as managed retreat will continue to be difficult without a national adaptation framework or national funding schemes. Creating a standardised approach to managed retreat at the national level will encourage community buy-in for long term avoidance strategies which involve relocation.

Step 9 and Step 10: Monitor, review and adjust

An important feature of DAPP planning is that it remains flexible, with processes embedded in the plan to allow for frequent review. For example, planners might consider the appropriate time to review a DAPP will be when a trigger is reached in a pathway. Effective monitoring of trigger points also needs to be managed through creating formal responsibilities. This could include determining the level of community involvement and self-monitoring. Communities may also evolve over the medium-long term. With such change, a community’s appetite for risk may change, requiring adaptation options to be adjusted accordingly.

Funding

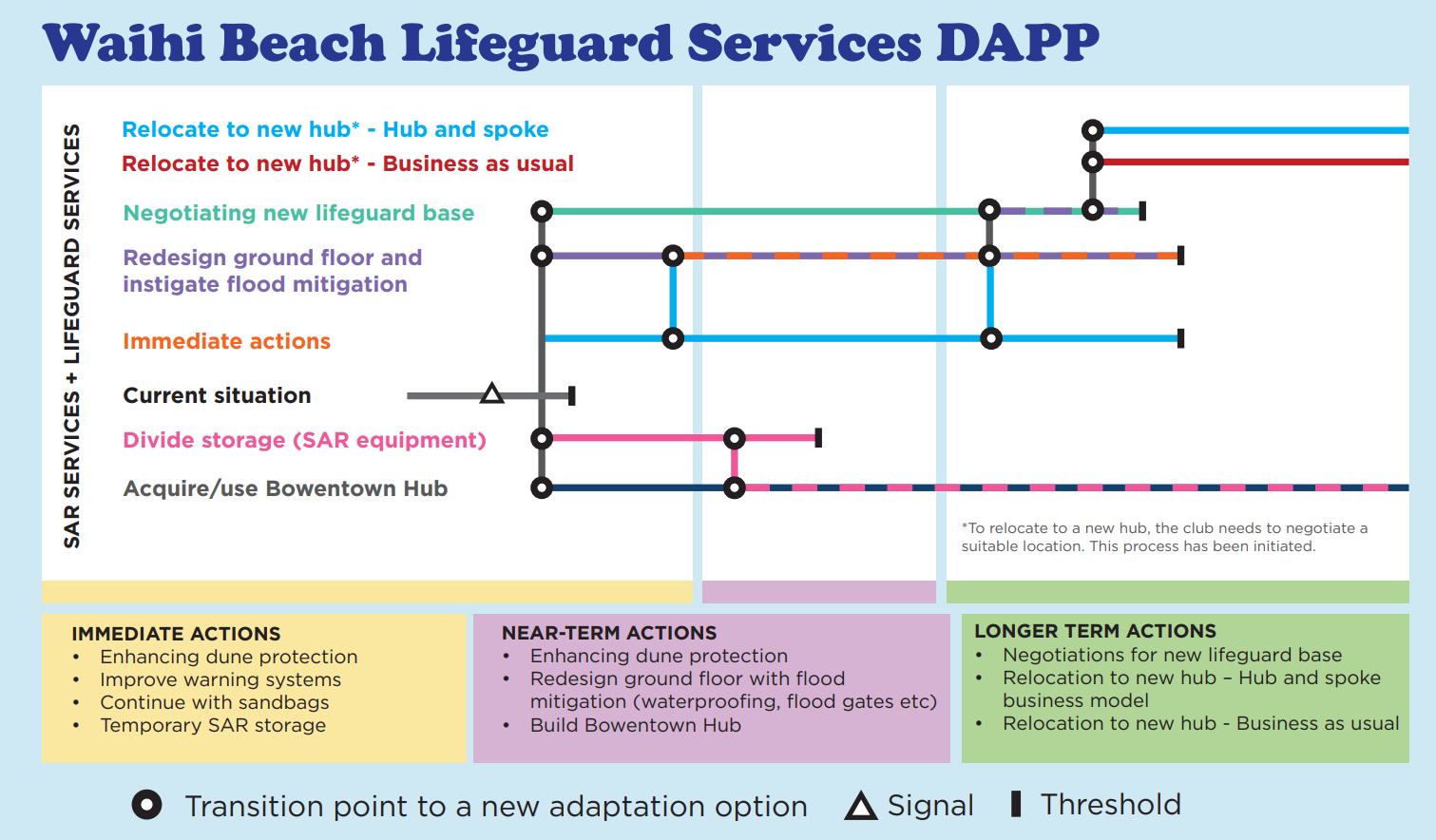

Funding DAPP planning may be a private or public undertaking for the benefit of entities, communities, districts or regions. As part of its Climate Change Action Plan, the Bay of Plenty Regional Council (BOPRC) has established a Community-led Adaptation Funding Initiative for its region. The Initiative aims to support communities and organisations that are ready to start planning for climate change, allowing such planning to be tailored to their needs and scale. Funding of up to $20,000 is available for applications for individual projects to support existing place-based community organisations, iwi, hapū, or marae in the Bay of Plenty region.

The Waihi Beach Lifeguard Services have been supported by this initiative in their efforts to plan for the future of the community surf club, located beachfront at Waihi Beach. Recent flood events and studies have highlighted that the club is one of the most climate vulnerable in the country. The club obtained funding from BOPRC for a series of workshops to assist with using DAPP to plan for building future resilience and ensuring the beach community is protected. The plan that has been developed considers actions that may be taken in the immediate term, near-term and long term:[6]

|

What can we do now to be prepared

Although DAPP planning offers flexibility and long-term planning benefits, practical social and financial barriers may complicate its execution. It is crucial that communities, businesses and individuals begin familiarising themselves with the issue of climate adaptation. At a minimum, we should take time to consider our values, vulnerabilities and objectives for adaptation.

Landowners across the residential and business sector should begin engaging with the technical information that is available. Some councils have already begun initiating plan changes to implement new policies and objectives to manage climate risks. We can expect that more councils will follow suit, especially given that progress is being made on national guidance. In its response to the FEC committee adaptation inquiry, the government has recently promised to deliver on an adaptation framework. We can also expect future plan changes to implement hazard management rules that will prohibit certain types of future development within areas exposed to climate risk. Communities and the business sector should begin preparing to provide input through lodging submissions when plan reviews become available.

Please reach out to one of our climate change and planning experts if you would like to know more.

Footnotes

1. Brent Edwards “Assessing local councils’ climate adaptation plans” (5 November 2024) National Business Review

2. Lawrence, J., Bell, R., & Stroombergen, A. (2019). A Hybrid Process to Address Uncertainty and Changing Climate Risk in Coastal Areas Using Dynamic Adaptive Pathways Planning, Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis & Real Options Analysis: A New Zealand Application. Sustainability, 11(2), 406.

3. Ministry for the Environment. 2024. Coastal hazards and climate change guidance. Wellington: Ministry for the Environment at page 103.

4. At page 115.

5. Auckland Council “Watercare Adaptive Water and Wastewater Infrastructure Planning”.

6. Bay of Plenty Regional Council “Waihi Beach Lifeguards Services” (1 May 2024).

This article was co-authored by Imogene Jones, a Solicitor in our Environment team.