The duty of officers under the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 (HSWA) is the focus of the prosecution of the former Chief Executive Officer of the Ports of Auckland Limited. That prosecution, brought by Maritime New Zealand, is the first of an officer of a major company in New Zealand and the decision of the Court (currently reserved following the hearing which ended in May) will be watched with interest.

Previously, prosecutions of officers in New Zealand have largely related to small, closely held, companies (or similar) where the officers in question were much closer to the day-to-day operations of the business or undertaking. By contrast, there has been limited guidance from the courts in New Zealand regarding the steps officers are required to take to discharge their due diligence duty under the HSWA where there is a greater functional separation between the PCBU and its officers.

Courts in Queensland and New South Wales have recently considered the application of the duty of officers under legislation which is comparable to the HSWA. Given the similarity between the officer duty in those jurisdictions and the HSWA, these decisions provide some insight and guidance about how the courts in New Zealand might interpret the duty as well as what steps officers may take to discharge it. Accordingly, these decisions will be of interest to officers in New Zealand.

SafeWork NSW v Doble

In SafeWork NSW v Doble [1], the New South Wales District Court acquitted the managing and sole director of a company in relation to an alleged breach of the due diligence duty under the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (NSW) (WHS Act (NSW)).

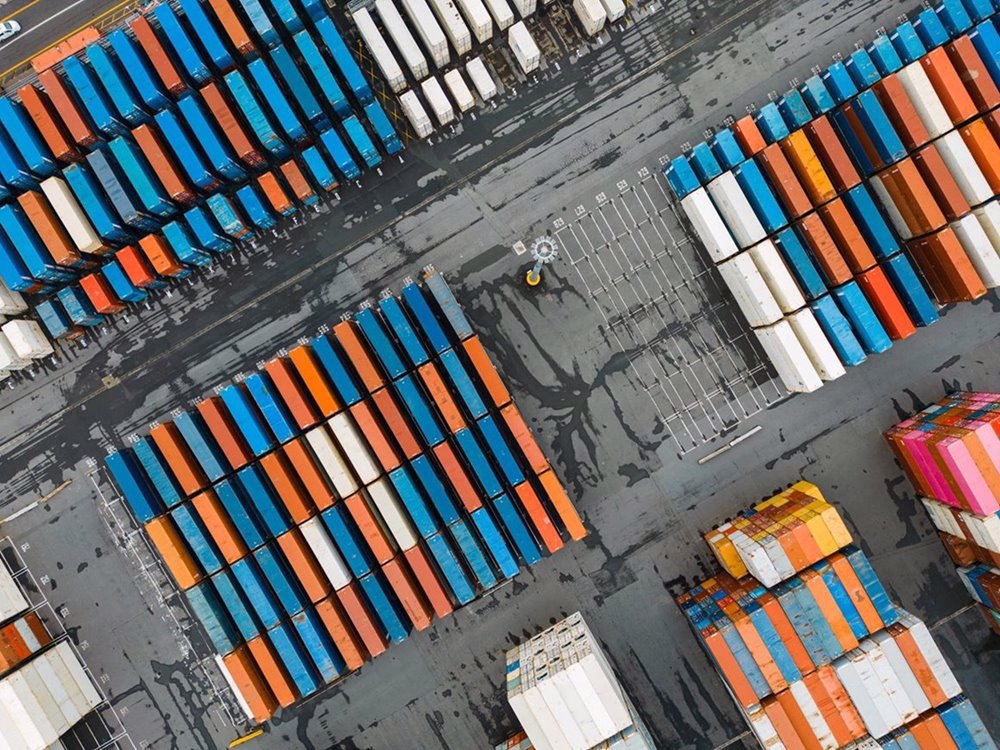

The defendant was an officer of a company that operated transport depots in New South Wales. At one of the depots, a person was struck by a forklift and suffered serious injuries. Miller Logistics Pty Ltd (the PCBU the defendant was a director of) was found guilty of breaching WHS Act (NSW) in connection with the incident, but Mr Doble was acquitted of the charge he faced that alleged he had failed to exercise due diligence to ensure Miller Logistics was complying with its PCBU duties by not:

- ensuring Miller Logistics had in place and used appropriate processes and resources to eliminate or minimise risks to health and safety from work carried out as part of the conduct of the business or undertaking; and

- verifying that certain processes or resources were provided, implemented and used by workers (as the case may be).

Guilfoyle v Walshaw

In Guilfoyle v Walshaw (which applied Doble) [2], the Magistrates Court of Queensland acquitted a former company director charged with breaching the duty of an officer under the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (QLD). The defendant was the former managing director of a PCBU which operated a zipline.

After the defendant had ceased to be involved with the company, a patron was killed and their spouse seriously injured when the zipline failed, causing them both to fall to the ground. The incident was caused by a failure to adequately maintain the wire rope grips which secured the zipline to the platform. The wire rope grips were installed while the defendant was an officer.

The prosecution alleged that Ms Walshaw had failed to exercise due diligence in that she failed, during her time as a director, to ensure that the PCBU complied with its health and safety duty. The reasonable steps Ms Walshaw should allegedly have taken were:

- putting in place and implementing a policy or safe work procedure requiring an engineer to design the cable structure, including selecting the terminations to be used to secure the cables by personally drafting, or engaging an external entity to draft, or directing a worker to draft the policy documents or safe work procedures; and/or

- putting in place and implementing a policy or safe work procedure requiring an advanced rigger, or an engineer install or oversee installation of the cables between platforms 3 and 4 by personally drafting, or engaging an external entity to draft, or directing a worker to draft policy documents or safe work procedures; and/or

- directing [an employee] to engage an advanced rigger or an engineer to install or oversee installation of the cables between platforms 3 and 4 and ensuring installation did not begin until this occurred; and/or

- directing [an employee] to terminate the cables between platforms 3 and 4 using swaged ends or other terminations that did not require regular tightening and ensuring installation did not begin until this occurred; and/or

- supervising or checking that [the employee] had engaged an advanced rigger or engineer to install or oversee installation of the cables between platforms 3 and 4 and ensuring installation did not begin, or was stopped, until this occurred; and/or

- making reasonable enquiries by consulting the Work Health and Safety Regulations 2011, and AS 3533.2-2009 Amusement Rides and Devices or AS 2076 Wire Rope Grips for Non-Lifting Applications, or Workplace Health and Safety Queensland or an engineer to:

- gain an understanding of the nature of hazards and risks associated with ziplines; and

- determine the qualifications required for a worker to install zipline cables; and

- ascertain the appropriate method to terminate zipline cables.

Our view

Both decisions contain similar discussions about what steps the courts expect officers to take to discharge their due diligence duty under the relevant legislation.

The factors which the courts found relevant to their assessment that the officers had discharged their due diligence duty can be summarised as follows:

- where a PCBU is not closely held, the officer of that PCBU cannot be expected to know everything occurring in the business and can be expected to delegate certain functions and activities to management;

- the courts placed emphasis on the fact that there were no resource constraints for management to seek advice or implement practices or processes related to health and safety;

- the officers met regularly with management who were responsible for, and knowledgeable about, health and safety matters and were entitled to rely upon the advice and representations they provided; and

- the officers were actively involved in their work overseeing the PCBU they were an officer of. For example, in Doble, this included the officer conducting semi-frequent site visits to the depots.

Also of note is the fact that the courts drew a clear distinction between the roles of the PCBU and officers in relation to health and safety under the relevant legislation. For example, in Guilfoyle, the prosecution alleged that the officer had failed to discharge her due diligence duty by not directing management to engage an advanced rigger to install the cable structure for the zipwire. The Court noted that this would have involved the defendant micro-managing the performance of the actual work by the PCBU and did not accept this action was necessary for an officer to discharge his or her due diligence duty.

Trent Forno of MinterEllison’s Brisbane office acted for the defendant in Guilfoyle in what is believed to be the first defended officer prosecution in Queensland. MinterEllison’s article in relation to the decision contains further detail and notes, in particular, that “other than in a very small business where there is little scope for delegation, an officer can partly discharge their WHS due diligence obligations by relying upon competent employees with specific responsibility for managing WHS. The decision also reinforces the duty of the prosecution to properly particularise the alleged breaches, supported by evidence which is relevant to exercising due diligence" [3].

Footnotes

[1] SafeWork NSW v Doble [2024] NSWDC 58.

[2] Guilfoyle v Walshaw MAG-00149166/21(1), 17 May 2024.

[3] Officer acquitted of alleged breach of WHS due diligence duty