The facts

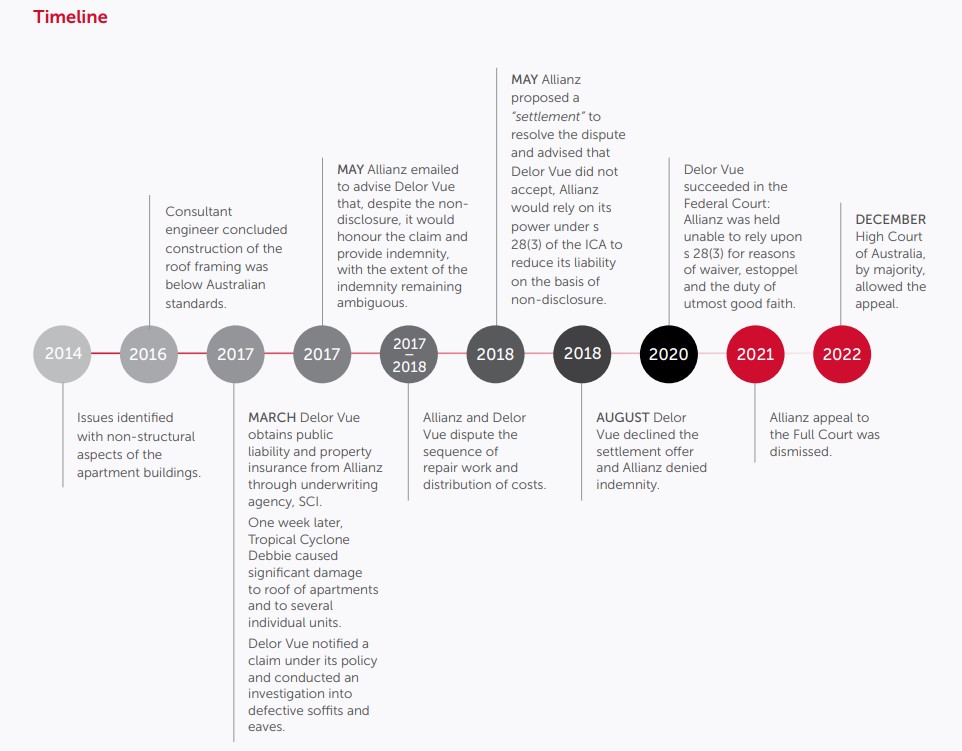

In March 2017, Tropical Cyclone Debbie made landfall in Queensland, Australia and caused approximately AUD2.5 billion in damage across areas in the south east of the state.

The cyclone caused substantial damage to the roof of the apartments at Delor Vue as well as to several individual units. Delor Vue notified a claim under its public liability and material damage policy. As part of that claim, Allianz, acting through its underwriting agent, SCI, became aware of Delor Vue’s failure to disclose pre-existing non-structural defects. However, Allianz initially responded positively. On 9 May 2017, it sent the following email to Delor Vue:

“Despite the non-disclosure issue which is present, [SCI] is pleased to confirm that we will honour the claim and provide indemnity to [Delor Vue] in line with all other relevant policy terms, conditions and exclusions.”

The email described the decision as one to “grant indemnity” but stated that there were two categories of damage: defective materials and construction of the roof and resultant damage. SCI said it would cover the second category but not the first. The High Court of Australia described the language used by SCI as “imprecise” and “unclear” and noted that the parties ultimately disagreed on the scope of application of the second category. It was uncertain whether Allianz contemplated that it would be necessary for Delor Vue and Allianz to reach agreement as to the roof repairs for which each party would pay before they were undertaken.

Following engagement of, and reports from, engineers and builders, Allianz discovered that there were more defects with the roof construction, including defects in the roof trusses and the manner in which they had been tied down. The result was that they were inadequate and could not be salvaged (although many remained undamaged by the cyclone).

On 3 May 2018, Delor Vue wrote to Allianz recording complaints, including an alleged failure by Allianz to state its position on indemnity “with any clarity” and allegations of breach of duty of good faith, among others.

That lead to a response from Allianz on 28 May 2018, in which Allianz set out its 2017 communication in full and proposed a “settlement” that required Delor Vue to pay for rectification of defects excluded under the policy, before Allianz would pay for the costs of repair or replacement arising from the cyclone damage.

Allianz’s offer expired unaccepted. It notified Delor Vue that its liability had been reduced to nil in reliance on s 28(3) of the Insurance Contracts Act 1984 (Cth).

Australian statutory context

The statutory response to non-disclosure and misrepresentation in Australia is clearer yet more nuanced than it is in New Zealand.

In Australia, s 28(3) of the Insurance Contracts Act 1984 (Cth) provides insurers with a right to reduce any claim made under the policy where there has been material but non-fraudulent non-disclosure or misrepresentation:

If the insurer is not entitled to avoid the contract, or being entitled to avoid the contract (whether under subsection (2) or otherwise) has not done so, the liability of the insurer in respect of a claim is reduced to the amount that would place the insurer in a position in which the insurer would have been if the relevant failure had not occurred.

We are likely to see a similar approach if the Insurance Contracts Bill comes into force.

Lower Court decisions

The Federal Court found that Allianz was entitled to rely on the statutory remedies for non-disclosure, subject to any election, waiver or estoppel. It ultimately found in favour of Delor Vue because it held that there had been sufficient waiver and Allianz was estopped from resiling, and in breach of its duty if it was to resile, from its representation.

On appeal to the Full Court, Delor Vue was successful on all four grounds.

High Court decision

The High Court of Australia, by majority, allowed Allianz’s appeal for the following reasons:

No waiver

Although the 9 May 2017 email contained a waiver of the s 28(3) defence, that waiver was conditional upon the acceptance of terms resolving ambiguity and was therefore revoked on 28 May 2018 when no resolution was reached. The majority held that a unilateral waiver could be revoked at any time on reasonable notice unless there were exceptional circumstances. According to the majority, to find otherwise would undermine other contractual rules including requiring variations of contracts to be for consideration.

No election

There was no election by affirmation. The majority confirmed that the modern approach applied where a party to a contract has two sets of rights that could not exist simultaneously: the choice between them should be irrevocable. However, in this case, Allianz’s decision to exercise a remedy under s 28(3) of the Act did not involve alternative and inconsistent sets of rights because s 28(3) operates only as a defence to reduce the amount of the insurer’s liability: “[w]ith or without waiver, the insurance contract remains on foot and reliance on the defence under s 28(3) is not immediately inconsistent with any of the contractual rights.” It distinguished this position from the decision to avoid a policy under s 28(2) of the Act. A promise not to enforce a legal right can be revoked at any time with reasonable notice to the other party, absent a variation to a contract by way of entry into a deed or a fresh agreement for consideration or the expiry of a limitation period. Further, Allianz’s early email amounted to taking steps that were inconsistent with an intention to rely on the s 28(3) defence, but it did not constitute full satisfaction of that alternative right i.e. payment of the indemnity.

No estoppel

Allianz was not estopped from resiling from its position in May 2017 because Delor Vue had not established that it had suffered any detriment (by way of adverse consequences, a source of detriment or even that it had lost an opportunity that was of real or substantial value) in reliance on Allianz’ representation. This approach aligns with the New Zealand Court of Appeal’s decision in Doig v Tower. Delor Vue alleged it was prejudiced because it lost the opportunity to obtain more in an early mediation than was offered by Allianz in May 2018 or that it lost the opportunity to carry out the repair work itself soon after the loss, rather than having a damaged building for over a year. Neither was made out on the evidence.

No breach of duty of utmost good faith

There is no free-standing obligation upon an insurer, independent of its contractual obligations, to act in a manner which is decent and fair so there was no basis to find that Allianz breached its duty of utmost good faith. The majority found that such a stand-alone duty would be inconsistent with the operation of existing legal doctrines and with the Act itself and would have “radical consequences” for an insured. The majority found that:

There is no free-standing general obligation upon an insurer, independent of its contractual rights, powers, and obligations, to act in a manner which is decent and fair. The obligation to act decently and with fairness is a condition on how existing rights, powers and duties are to be exercised or performed in the commercial world.

Although the duty is codified in s 13 of the Act, the majority noted that it is an “instantiation of the centuries-old common law “duty of utmost good faith””.

New Zealand position and takeaways for insurers

The High Court of Australia’s finding that there was no extended or novel duty of good faith on Allianz not to resile, without a reasonable basis, from representations to an insured about a claim under its policy is relevant in New Zealand. The Court’s treatment of general contractual principles such as waiver, election and estoppel serve as a good reminder of how New Zealand courts would likely approach the issue. The FMA’s expectations might well differ where retail customers are involved.

The case also provides an insight into how the New Zealand statutory regime may well operate if the Insurance Contracts Bill is brought into law.